Democracy 4 Interview – A Game About “The Fantasy of Influencing Our Political System”

Like many people today, my first experience with Democracy was a mixture of excitement and frustration. Positech Games’ Democracy franchise gives players the role of an elected official enacting their political agenda in one of several selectable countries. It’s a game that gives players the power fantasy of dominating an electorate with popular proposals, but also the fury that comes with being unable to do what’s needed because of a handful of stubborn power brokers.

My first foray into the series was Democracy 2 — released in 2007, still gleaming with that early-2000s aesthetic of earnest professionalism with an occasional digression into satire. It felt like a game made for fans of West Wing or maybe Office Space. This was back when our institutions had limits to their absurdity, a reality of the past the developer admits dates the previous entries and served as motivation for making a new installment — Democracy 4 — expected later this year (Democracy 3 was released in 2013).

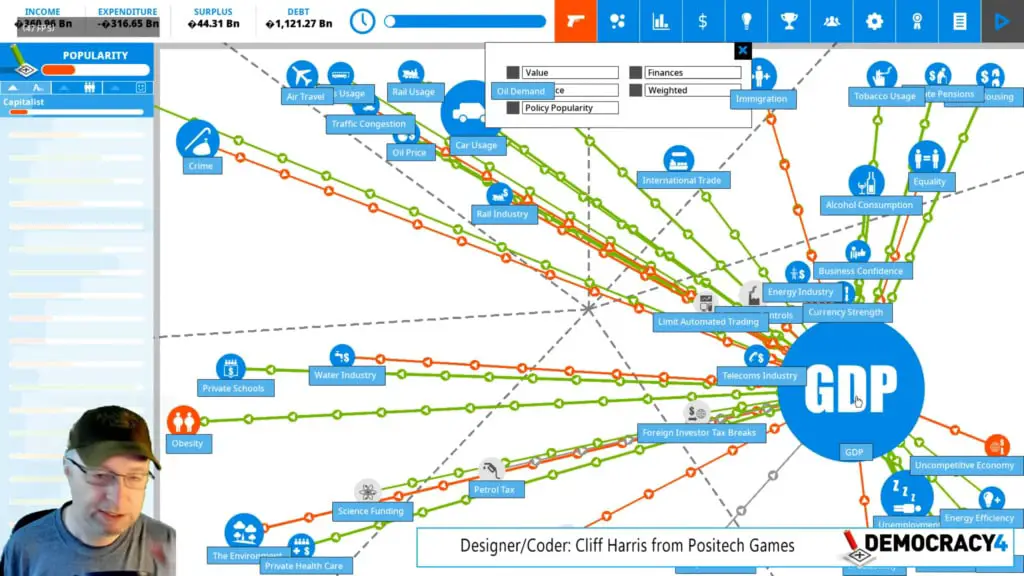

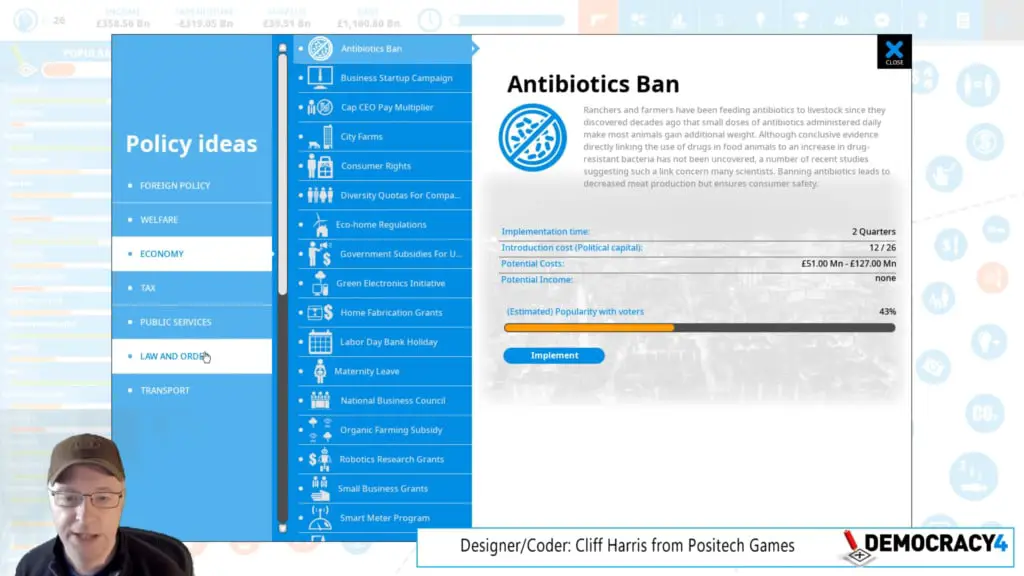

Democracy is an in-depth political simulator, and I don’t think there’s any other game like it right now. Many games have “political” decision-making on the sides, but this series puts it front and center. Governance is presented to the player as a series of issues represented as buttons on a glorified spreadsheet. Each button is separated into seven different sections depending on their general category — such as “Law and Order,” “Transport,” or “Economy.” These buttons represent policies (white buttons), data points (blue buttons), problems (red buttons), or successes (green buttons) in your fictional society.

Players can influence policies directly, but the other three change based on how the player’s policies indirectly impact each of them. For example, you could choose to increase your society’s “alcohol tax” to 100 percent, and maybe you’d eliminate “alcoholism” as a problem. Still, you’d also decrease the “equality” data point and potentially diminish your country’s “GDP” data point by a tiny sliver.

Additionally, every policy has an impact on voter demographics. Your new alcohol tax might earn you support among parents and the religious, but liberals and conservatives won’t be thrilled with your high tax rate creating inequality. Losing their support may cost you their support in the next election. If you lose an election, the game is over.

Like many popular strategy games in the past decade, Democracy doesn’t set clear goals. The game lets players decide their own objectives. Do you want to transform the United States into an environmentally friendly socialist paradise? Go for it. Do you want to eliminate the income tax and reduce the size of the government by 60 percent? Try it. Do you want to implement a draconian surveillance state? You can do that. But with any of these objectives, you’ll run into the same problems elected officials deal with every day. Your cabinet members could jam up your political capital, voting demographics may turn against you, or maybe a debt crisis or terrorist attack will change your priorities.

Some of Democracy’s maintains a veneer of cheeky humor, but for the most part, Democracy is meant to be an accurate simulation of modern politics. The purity of Democracy’s simulation is primarily because of Positech Games’ developer Cliff Harris.

Harris likes to say “we” a lot when he talks about his games, but he’s a studio of one that occasionally works with another programmer or artist when necessary. Harris describes himself as someone who has been “all over the political spectrum,” but when creating the Democracy games, he didn’t want to make a political statement. His intent is evident in the game’s mechanics. He wanted to give players the experience of being an elected official and facing the same problems these leaders see every day.

For many people interested in local or national governance, it can be frustrating to see there are not a lot of opportunities to influence our politics. The few opportunities that do exist are not what we envisioned—sitting in board meetings for three hours while unpaid town councilors learn how Zoom works weren’t mentioned in the blueprint for revolution. Maybe that’s why I have 20 hours played in a game where you can finish a single four-year term in 10 minutes or so — if you know what you’re doing.

There were several reasons I wanted to talk to Cliff. Was his game popular? Do young people play it? Why did he make the game? I was thrilled when he accepted to chat, despite being a guy who rarely does conventions or interviews — although he does maintain a YouTube channel where he talks about the game. This interview was recorded, but only my microphone was saved. Below is a transcript based on notes.

Arthur Augustyn, Noisy Pixel: When I was younger, I played every new release and enjoyed them enough. But as I’ve gotten older, I’ve spent more of my time on massively complicated strategy games like some of the games you make. Have you had a similar experience in your habits, and does that influence the type of games you make?

Cliff Harris, Positech Games: There are two types of games I play right now. The first is first-person shooters. I play Battlefield 5 for about an hour a day with other game developers. That’s really fun because it’s so different from the type of games I work on all the time. I enjoy it the same way other people who play that game.

The other type of games I play are strategy games — similar to the types of things I make. When I play those games, I analyze them like a game developer. If I see a bit of poor design like a long loading screen — something that might be inconvenient for a typical player — it drives me crazy. That’s the type of thing I would work to fix when I was working in triple AAA game development.

AA: How much of that is common among developers compared to your experience specifically? Do you think you’ve always been that way, and did that bring you to an appreciation for highly strategic games that are very complicated?

CH: Games have always been about living some type of fantasy. Battlefield is an easy example. I always envisioned I’d either be a game developer or… like a powerful commando or something.

AA: That’s really options 1 and 2 for all gamers, I think.

CH: Games are all about providing a fantasy for people. When I was making Democracy, I noticed everyone has an opinion on politics and how things should be, and everyone is disappointed with their elected officials. Everyone thinks they’re doing a terrible job. There’s really no one who’s very happy with the person in charge of their town or country. We know our individual votes don’t sway the world very much, so Democracy was about letting people live the fantasy of influencing our political system and fixing everything. In a way, it’s monetizing the righteous anger that exists on Twitter.

![]()

Who plays these games?

AA: Democracy 2 came out in 2007, which was a number of years before the Twitterverse became a formidable political force. Democracy 3 came out in 2013 — which I think is still a little bit before the massive interest in politics among young people. Have you seen more people interested in these games recently?

CH: I don’t have a lot of data on who plays my games. I don’t do conventions or anything like that. I’m 50 years old right now, and I always believed — based on forum interactions and the few questions I’d get — that everyone who played my games were people like me. They were older, had a degree in economics or something, and they had a similar background to me. A number of years ago, I did a convention where I showed off one of the Democracy games, and I thought, ‘Well, no one is going to sit down and play this game in this environment,’ but there were a few who stopped and played it. They were all young people.

AA: Can you give me an idea of when this story happened?

CH: It must’ve been eight years ago. To be honest, I don’t remember when Democracy 2 or 3 came out.

AA: Democracy 3 came out on Steam in 2013.

CH: Then it must’ve been around 2012 before Democracy 3 was released. It’s interesting because the world has changed a lot since then. Young people have never really been politically engaged, but I’m seeing more and more young people interested in politics. A lot of that is coming from Twitter — which is frankly terrible. I’m on Twitter for game development stuff, and cat photos, but there’s really nothing you can post that won’t upset people. I think some of that is because the world has gotten more extreme, at least on the internet.

We have an expansion for Democracy 3 called “Extremism,” which continues to be our most popular expansion, but since it came out so long ago, it hasn’t kept up with our definition of extremism in the modern world. Back then, I didn’t even think to include a policy like “build a giant wall on the border.” I think people would have thought the game was a parody which we wanted to avoid. It was important to me for the game to represent the real world.

AA: I wanted to ask about this relationship between young people and niche topics like politics. To give you context, I’m 28, and I’ve liked your games for a while. I’ve always thought with the advent of the internet; the biggest change was there was no longer a consolidation of culture. It has become easier for people to find niches and get really into one thing without getting ridiculed — not that I know what the world was like before I was alive. I’ve always found it easy to find things that are “nerdy” and find millions of people who are into the same thing.

There are a number of games — including yours — that are benefiting from this shift in culture. Games like Cities Skylines — which was pitched as a Sim City competitor — but its fanbase is really aspiring City Planners and Traffic Engineers. There’s an entire Facebook group called New Urbanist Memes for Transit Orientated Teens, which has nearly 200,000 people in it talking about traffic planning and Cities Skylines…

CH: Yes, the developer of Cities Skylines made another game before Skylines called [Cities in Motions] that had an in-depth traffic system, so it wasn’t a huge surprise Cities Skylines was very good at that too. There are not a lot of games that provide those fantasies to players.

![]()

Is this game a critique on politics?

AA: I wanted to ask about how some of the consequences in your game make it seem like a “parody.” There is a bit of humor in your games like the loading screen text will say “rigging elections” or “avoiding real debate.” How much of that is cheeky fun, or was there ever an attempt for the game to be a parody or a commentary on the system?

CH: I try very hard to be politically neutral with all the text in the game. I’ve been all over the political spectrum across my life. I am very sarcastic, so there are some quips in loading screen text and elsewhere, but when it comes to the policies in the game, I don’t input my own views because I think players get turned off by it. The goal of the game was to provide a tool — kind of a toy box — for people to play with the system and get an idea of how things would be impacted by different policies and ideas.

AA: In a way, your game is closer to a fun “model” rather than a complex “game.”

CH: Yes, we wanted it to be representative of the real world.

AA: With that in mind, I wanted to ask if you learned anything while working on this game or if you wanted to teach people specific things. There are some policies that seem to have no drawbacks whatsoever — such as “food stamps” or “bus subsidies.” They’re not very expensive, they make people happy, and they have a positive effect on the economy. On the other hand, there are policies that seem totally useless like “business startup campaign,” doesn’t seem to do anything but throw money into a hole.

The other one I noticed is on “abortion” policies, you can have “two doctors’ approval,” which is relatively liberal access to abortion, but you can go further and have “on demand.” The only difference between those two policies is a very tiny sliver of positive approval among “Liberals” who like it a tiny bit better, but also a massive negative swing for “Religious” and “Conservatives.” Was that motivated by what you learned in the world, or is that part of a commentary?

CH: There are unique modifiers for each country in the game on a handful of issues. For example, in the United Kingdom — where I live — abortion isn’t really an active topic. It’s an issue that’s sort of “settled,” I guess? It’s very different in America. It can be difficult to get a true sense of what the public sentiment is for different countries. Imagine going to the internet and searching “views on abortion in America,” you’ll get a lot of heated debate, but it’s not necessarily representative of what people think on the ground.

Alcohol and gun control are other examples. I’ve lived in the UK my whole life, and I’ve seen three guns ever. Once at the airport, once outside of parliament, and once when I went to shoot clay pigeons a number of years ago. The gun control conversation doesn’t really exist in the UK, whereas conversations about property values have been dominant here for a number of years, so that has more sway on the electorate than if you pick a different country and change the same policy, you’ll get a different effect.

AA: For context, the country I was playing with the abortion policy was Canada.

CH: Right, so abortion is not much of a conversation in that country, so the values are different on that specific issue. There are not many of those country-specific modifiers, but the game does have a few of them.

For the “business startup campaign,” I don’t think it does anything except — over a very long time — it will make people more capitalist. We wanted to make a portrayal of the real world where there were consequences if you tried to shake things up very dramatically. If you tried to create a capitalist society in a country like France — where people are generally not very capitalist — you’ll create discontent among the electorate, and that will lead to extremist groups forming and your character may get assassinated. This was meant to provide a consequence to players who wanted to radically change the system. The reality is you can’t do that without consequences.

We released an expansion called Social Engineering so you can set up the public to accept radical changes a bit more readily, and “business startup campaign” is an example of one of those social engineering policies that will prepare the public for a new mindset. Obviously, some groups are less likely to cause a threat. For example, if you really upset the “elderly” demographic, it’s unlikely they’ll try to assassinate you. The point of the Social Engineering expansion and its mechanics were to get people to think about long-term. If you want to dramatically change a society, you have to think about planting a seed and creating change over a long period of time. Obviously, politicians don’t typically think in the long term.

![]()

Is Democracy a game or a simulator?

AA: Assassinations is one of the few fail states in the game. I think the only way you can lose immediately is by getting assassinated or having a debt crisis. You can lose an election too, but those two examples will end your game immediately. I think my first ten games I lost because of a debt crisis. Now when I play the game — no matter what country — I cut corporation tax, implement small business grants, and invest in technology because that seems to prevent a debt crisis. I wonder how much of that has affected my real-world views because I don’t remember being terribly concerned about a country’s debt ten years ago. When you were designing the game, did you think about where the source of difficulty/challenge would come from in the game?

CH: There’s really only one way to lose in the game, which is losing an election. Things like assassination were put in the game to add a consequence to players trying to radically alter things very quickly. A debt crisis is bad, but only because it makes you very unpopular, and you lose the next election.

AA: Correct me if I’m wrong, but if your debt gets to the top of the graph, you get a prompt that says, “you don’t have any money,” and the game ends, right?

CH: I’m not sure. I haven’t heard much feedback on that problem.

AA: Maybe you’re too good at your own game. I think I’ve seen that screen many times.

CH: It’s difficult because when I play the game, I have to turn off my knowledge of its design and go into it blind to see if players can have a good experience with it.

AA: With that in mind, did you try to make fail states — like a debt crisis — not as bad as it is in the real world? From what I understand of countries that go into debt, there comes a point where there’s nothing you can do.

CH: It’s funny because a debt crisis is a real-world example of poor game design. In game design, you try not to have virtue circles or death spirals. A debt crisis is very much an example of a death spiral — it gets worse and worse, and at some point, you can’t do anything about it. That’s frustrating to a player, but that’s how it is in the real world so that’s how it is in the game.

AA: I think I like the virtue circles and death spirals in your game because it feels real. When I first played it, I tried to get my friends into it, and they said it was too difficult. I had a game where I won the election a few times in a row, and by the fifth election, I had totally broken the game, and my voter turnout out of 100 percent was shown as “-1.#J%” so I think I broke the game. I had become a cult leader beyond measurement. I think it is representative of some elected officials who can do anything, and they’re still beloved. Do you prioritize making the game an accurate “model” that represents the world right now?

CH: There are a lot of design decisions we make to replicate the difficulties of the real world and how those problems change each year. For example, when I was growing up, “money printing” was called “money printing,” and it was bad, and no one would ever do it. Now it’s called “quantitative easing,” and has some complicated effects on our financial institutions. It has become a big enough issue in mainstream politics that I want to include it in Democracy 4, but it’s a difficult decision.

I went to London School of Economics, and I know a bit about things like interest rates and how they impact property rates or savings accounts and etc. The problem is you can’t really have an accurate model of quantitative easing without designing an interest rate mechanic. The problem with that is the game becomes too complicated for any player that doesn’t have a finance degree. They’ll try to change things, and they’ll fail without knowing why.

AA: I wonder if there’s a subset of your audience that would pay for an expansion called Democracy 4: Interest Rates.

CH: I don’t know. Again, games are meant to be a fantasy, and for many people, they want that realistic level of challenge. I think that’s why there are a bunch of farmers who play Farming Simulator. There is an interest in those experiences.

![]()

The appeal of complicated simulators

AA: I read an interesting insight from former Democratic Presidential Candidate Andrew Yang who said video games are often very popular for young men specifically because it’s the only opportunity they have to utilize all their skills.

CH: Yes, games can be a good tool for introducing people to a more complicated field. We’ve sold a few enterprise copies to the United States Department of Defense and other tangential organizations. They were using it to explain how small decisions can have ripple effects in a whole society.

AA: Wait, Democracy 3 is used by the U.S. Department of Defense?

CH: We were contacted for a potential bid — the government has a budget for modeling software for teaching tools — but the bid wasn’t accepted, so no, it’s not used, and they did not purchase any copies. There are a bunch of stories like this. The Yemenis Government wanted to purchase enterprise copies to use as a teaching tool for students in the country, but that was a while ago, and they’re busy with a civil war now.

![]()

Positech Games background

AA: Is that a main revenue source for you? You’ve been an independent game developer for a number of years, and you use the phrase “we” a lot, but if I’m not mistaken, Positech Games is practically a solo studio. Do you make a decent living?

CH: I work with one programmer — Jeff. I do a lot of low-level programming. I’ve been a game developer for a long time, so I use tools most developers do not use these days. If I was coding in Unity, I could throw a stone and find a developer I could work with, but I don’t. I do most of the programming for my games, and I work on them all the time. You could say I am a workaholic, but I really love what I do. For example, today is Sunday, but I don’t see it as “the weekend.” I work on my games every day.

I don’t “need” to release a game every year, but I do release about one game a year. Some of them have been very successful. Democracy 3 sold 800,000 copies — mind you not all of those copies are at full price — but it’s enough that I could honestly retire. I don’t want to retire, though. I love making games. Even if I had a million dollars and never had to work again, I’d still make games.

AA: On your website, you say you donate money to charities like War Child and building schools in Africa.

CH: Yes, there was a convention one year where I saw War Child give a presentation, and it was very good. I was very motivated by how much of an impact could be made with so little. I donated $15,000 for the construction of an entire school in 2015 in Cameroon.

AA: Yeah, on your blog, you show a photo of the old school, which I think most people reading this would see as a grade below the treehouse they had in their backyard.

CH: Right, it does make a huge impact on these communities, and it doesn’t cost much on my end. It’s basically a week’s worth of revenue around Christmas time. I’ve actually donated again more recently for a second school, and it’s a full school. It has full plumbing, roofing, and supplies. So, I could donate that same amount to a local school and barely make an impact but get my name in the paper, or I could put it somewhere more meaningful.

AA: Wrapping up here: I know Democracy 4 is mostly done, do you have a date in mind? Is it impacted by the global pandemic at all?

CH: Not really. We’ll sell the game on our website first, and we’ll come to early access on Steam. We definitely want to get it out this year while the U.S. election is going on.

AA: Part of me wishes I asked more about the game, but your YouTube channel has a lot of content showing off the game and giving an idea what it’s like, so people can check it out if they’re interested. Is there anywhere you want to plug? It sounds like you’re not on Twitter.

CH: I am on Twitter, but I also have a blog where I talk about what I’m working on so I‘d direct people to that.

This post may contain Amazon affiliate links. As an Amazon Associate Noisy Pixel earns from qualifying purchases.